|

|

#1

|

||||

|

||||

|

Magellan Venus - designing and building the old-fashioned way

Serious designers - standing by for better ways of doing this. For duffers (like me) note that you can do this too.

I built several spacecraft models as part of a solar system tour set of significant spaceprobes. For Venus, I needed a Magellan spacecraft - producer of the first detailed maps of the surface of Venus. I was not impressed with the only commercial offering - mixed media, not much detail, and looked a bit stumpy. So, I designed and built Magellan from scratch (available from the Lower Hudson Valley Challenger Center - jleslie48.com - courtesy of Jon Leslie). To start with, you need both a good dimensioned drawing (plans, blueprints, diagrams) and as many photos of the full spacecraft and (exposed) instrumentation as you can get. Magellan line drawings    The goal is to end up with a (nearly) flat view of every surface. However, once you get the major pieces started it quickly falls into place. The key is matching up the edges. Odd shapes become defined once you have all the edges correctly sized. For Magellan - it starts with the high gain antenna dish (HGA). It's 12 feet across - so 3" in diameter in 1:48 scale (144" / 48 = 3"). However, it's modelled with a cone. To make a simple cone just slit a circle from the center to the edge, then overlap the cut edges. The more overlap, the steeper and sharper the cone - and the more its diameter shrinks from your starting circle. You can calculate the exact figures - Jon has a tool availble at the LHVCC (check the FAQs) - or you can just add a bit (I used a 10% increase) to the circle and fit it by eye.  With one major part started, it's back to the diagrams. The HGA is mounted on a disk (the support base) so we'll need a circle for the bottom and a rectangular strip to make the edge band. Measuring from the diagram is simplified if you adjust the printer settings to give you a scaled drawing (make the dish 3" across), otherwise you'll have some tedious calculations - support base diameter (from drawing) divided by HGA dish diameter (from drawing) times 3" scale size of the dish gives you the scale diameter for the support base. This is the basic way to get all the unlabeled dimensions from a drawn plan. Once you have the diameter of the support base circle, you need the height of the edge band from the drawing. Length of the edge band part (a simple rectangle that will wrap around the base circle) is the old equation: pi times diameter (3.14 is a handy number). With some basic parts defined, it's time to figure out how to join them. If you've built some models already you're familiar with several ways. Basically, it's either edge-to-edge gluing (strength OK for small parts but demands a perfect fit), or some variation of attached or added tabs (flat surfaces provide strongest bond and allow some adjustment of the fit). In my case, I opted to put attached triangular tabs on the top and bottom of the edge band and extend it's length with an end tab. The band is glued into a circle (use of an integral tab causes a slight bulge and hard spot - you can eliminate this by using a separate piece glued across the joint but that adds another part and building step). The triangular tabs are then bent inward and capped with the bottom circle and (later) the HGA. So, three parts and the basic structure is formed. The next step is designing the secondary reflector and its tripod support. Back to the drawing to pull the diameter of the reflector and the length of the tripod legs. The basic part is then a "spider" with the legs attached radially to the edge of the circle. In the case of Magellan, each leg actually has two struts so you add in the struts from the edge of the circle, midway between each leg attachment and extend them to meet the end of the leg. Once the six struts are drawn in, erase the original leg - it's served its purpose in giving you the right length and orientation for the actual struts. So, we've got a basic HGA assembly. It's time to put some detail in place to make it a model and not a cartoon (though most of my designs are on the edge). For this we'll need pictures - lot's of pictures.  To be continued ... Last edited by Retired_for_now; 06-21-2009 at 02:51 PM. |

| Google Adsense |

|

#2

|

||||

|

||||

|

Google (images) is your friend

You can surf NASA (or ESA, JAXA, whoever launched the satellite) and the mission site for images - or you can use that wonderful (non-evil) tool of world domination - Google. Search terms: magellan spacecraft (or spaceprobe) brings up pages of thumbnails to vastly speed your search. You're looking for detail and color in the photos.

For the HGA, the diagrams and photos both show the low gain antenna (LGA) on top of the secondary reflector, the prominent shape of the secondary reflector on the underside of the tripod, and a feed horn down in the bottom of the HGA dish. The LGA is a simple cylinder - so the part is a rectangle (height scaled to the drawing, length pi times scaled diameter) that you roll up. For a display model (versus the museum editions I see gracing other's build pages) close is good enough. For smaller diameter cylinders - it's also useful to have some extra overlap on the end tab to make assembly easier (or wind from several layers of lightweight paper). Once wound, the part will be edge glued to the flat surface of the tripod's top. Lines, color or patterns add visual interest (and hopefully functional detail) to the part. The underside of the reflector can be left flat as is (remember - close enough?) or you can make a small cone and glue it on for 3-D detail. Again, I used about 10% over the diameter of the tripod's center and overlapped the cone's cut edges until it fit. Finally, the feed horn in a parabolic antenna usually sits on a flat bottom - the area "shaded" by the secondary reflector. Rather than add a part for the flat (and struggle wtih keeping it perfectly centered in the HGA during assembly) I simply added a circular cutout to the center of the HGA dish, allowing the bottom of the support base to form the flat section. Creating the feed horn cone is a more extreme example of what we did with the HGA dish. We're making a frustum (cone with the tip cut off flat). The part is made by drawing two concentric circles and using a portion of the circular band between the circles. Once again, you can do exact calculations for the base diameter, total height, and top diameter desired (see jleslie48.com under the FAQs) - or you can use TLAR. The finished part will be edge glued to the center of the flat support base.  How far you take this step of adding detail depends on your time, motivation, and intent. It's probably possible to never get around to building the model - just endlessly keep adding detail and refining the design. Me, I'm hopefully designing things that get built (educational focus "for the children" - that's my story and I'm sticking to it!). For me, that imposes a limit on the number of parts and fiddly bits. To compensate, I do continue to refine the designs - but I add detail and visual interest with graphics and simple 3-D pieces, not major subassemblies. So, time to move to the next major part - the forward equipment module.  To be continued ... |

|

#3

|

||||

|

||||

|

Making boxes

The Magellan equipment module is a simple box. The first step is to pull its dimensions from your drawings. Unfortunately, its obvious from the pictures that the box's width and depth are not the same, and the best drawing only shows one side. So, we can easily pull the dimensions for the height and depth (narrow side), scaled for your drawing. The width requires some ciphering.

Looking at the line drawing at the bottom of the previous post gives you a rough idea, but the depth is projected at an angle so you can't directly measure the relationship. You can, however, draw a vertical line across the HGA dish's diameter (12') and use that as your comparison. So now we can draw out the four faces of the box.  Fit issues come to the fore. The best way to make sure parts fit well is to draw them connected - this is the advantage of graphic "unfolding" programs like Pepakura, they start with all the edges connected (forcing them to match) then unfold them to flat panels for cutting out the parts. Those of us still in the stone age (pencil age?) need to do the unfolding in our heads and check and recheck the fit with measurements and test builds. So, a basic box lines up the four sides, joined at the long edges, and connects the free ends with a tab. The top and bottom pop off of either side and connect with one to three tabs on the edges. However, when building a model there are things to consider before you give your box a top or bottom. Making a complete box will (usually) ensure the part is square (or whatever angle you're after - more on this when we build the bus), and it will give you lots of gluing surface. However, the tendency of the flat panels to bulge out may make it difficult to get a good fit around the edges. If you apply glue only around those edges you've wasted all that good glue surface in the middle. Leaving out the top and/or bottom (if not visible in the final model) solves the problem of getting good tight edge seams - but also makes a less rigid part. You can solve that problem with guide lines printed onto the model showing where to place and align the part - but this will also demand precise assembly. The glue joint will also be weaker (and excess glue more exposed) since you are gluing only with the thin edge of your card stock. This is OK for small parts, but not for major (structural) parts of your model. An intermediate solution is to put tabs on the top and bottom edges of each face, providing more gluing surface while still ensuring you get a tight join. When assembled, the part becomes a hollow "tube." The edges of the tabs need to be angled so they don't overlap when the box is assembled or you will get gaps at the corners. Careful selection of this angle (45 degrees for a right angled box, in general half the angle of the finished face joins) allows you to use the tabs to help make your box more rigid and hold the correct angles when assembled. Now you have a blank part - time to think about graphics. To me, this is the best part of card modeling. Refer to your photos for colors, patterns, and low relief details. You can just make a colorful part (bright, solid color) or go completely nuts (see Gearz thread on the 2010 Leonov). On to detailing. Whether to use printed graphics for detail or to build and add detail parts depends on the visual impact you're after. I generally make detail parts for significant functional parts of the spacecraft or for items that project more than a few inches (scale, the thickness of cracker-box card stock). The Magellan equipment module is a simple part - with only the star tracker and thermal control louvers visible. It took some staring at the various pictures to figure out the size, number, and placement. Another advantage to doing your own model is the ability to make changes as you get better information.  I elected to build the star tracker's barrel (cone) since it's both an obvious and significant piece of equipment. The louvers are simply printed. You can easily make them appropriately 3-D by printing another copy of the module, cutting out the louvers, laminating them to one or two layers of thick card, then gluing them over the printed areas on the model's module. Even if I'm designing a 3-D part, I like to also print the details as well rather than leaving a blank space. This is makes a good assembly guide, showing where to place the part, and gives you the option of making a simpler model (lack of age or patience?). Make sure to put in locations for additional parts (star tracker mounting, solar array shaft, radar altimeter wave guide) as well. You can add detail if needed, and if you can find a good picture.   So much for square boxes - how about a decagon?  To be continued ... ? |

|

#4

|

||||

|

||||

|

Geometry? Bah ...

Drawing regular polygons is challenging - unless you've got really good software or enjoy micro-measuring angles. However, it can be done with simple drawing programs.

So, a word about software. Any drawing program that produces lines and a few simple forms can give you good results with reasonable effort - though sometimes you have to sneak up on it. I draw with the Microserf drawing tools, usually in Powerpoint - for no other reason than decades of hours mis-spent making slides and briefings. The most powerful function you need is a copy and paste, followed by the ability to rotate lines and figures without distortion. This allows you to make identical panels - the hardest thing to do by hand and the most important factor in ensuring a good fit of your parts. So, back to polygons. I have a limited number of polygon drawing options, none of which is fixed in shape. To ensure I have a regular shape I invariably start with a circle and a set of lines through its center as a set of crosshairs. The polygon gets centered in the circle and gets manipulated until its faces or vertices (points) just touch all round. Once set, I can resize the entire figure by a fixed percentage to get the size correct (whichever dimension you have). For Magellan, that's the distance across opposite faces, since that is available in the drawings. Unfortunately, I don't have a decagon so had to overlap two identical pentagons (copy and paste, remember?) and rotate one until I got ten equal length faces. In this case, I actually just flipped the copy to get the correct rotation. Tracing the desired ten faces with individual lines and grouping them as a figure yielded the decagon shape I needed. Then, back to check the dimensions and resize as necessary.  With the basic shape created, it's time to decide how to make the box that will model the bus. My rules to ensure the best final fit are to have as few parts as possible and to have as many of them attached (rather than glued on separately) as I can. Ideally, the bus needs ten outer and ten inner faces and top and bottom "rings." Check out Ton's Voyager model for one way to do this. You can attach the outer panels to the top or bottom, but there isn't enough room to do the same with the inner panel (even if you attach half to the top piece and half to the bottom). Since I like to keep things simple - I cheated. I modeled the outer panels but used a solid top and bottom with graphics for detail. This also makes attaching the forward equipment module easy since it has a flat surface to sit on. To ensure a good fit I made identical top and bottom panels, then attached all the outer panels to the top. You can also create a "string" of all ten panels and wrap them around the edge - I avoid this approach since (invariably) some minor error, variation, card thickness, or fold distortion makes the part end up a smidgen short. One panel was created to fit the face length and measured depth of the bus, the copied, rotated and moved into position for the other faces. At this point I noticed my decagon was not perfect. As I draw, I work at the highest screen magnification that allows me to see the part I'm working on - and I had a few misses. However, some judicious and symmetrical tweaking of the panels (fix one, then copy and paste again) gave me a result that is satisfactory to the eye (if not the micrometer). The lesson here is you can get it as good as you need to - it's just a question of how much time you're willing to put in.  The box was designed to fold into an open box, then have the bottom fold into place - that way any building misalignment (and glue seams) would be on the bottom of the model and so less obvious. So, back to the pictures for graphic details. Most spacecraft are wrapped in various types of insulation - obscuring detail but adding color. You can design your model as "in flight" with lots of colorful and textured insulation, or more naked to show the structure and instruments. Magellan is completely covered with close fitting white blanket insulation and has few external instruments (primary sensor is a radar altimeter using one horn antenna and the main dish) so the choice was fairly easy. The thermal control louvers are about the only exposed structure and are modeled with simple graphics. They could be modelled 3 dimentionally by simple printing another part, cutting out the louvers, and mounting them over the graphics on a piece of thick card (an approach I use to add 3-D to other's models). Additional graphic detail is still needed to better show the fuel tank and its supporting structure within the bus, as well as insulation texture and the color of the taped seams - on my list for future revision.  The last thing to add is the medium gain antenna (MGA) that attaches to the bus (and mark its position on the bus for assembly - where possible I try to mark and label where things go to simplify construction - especially since I write the assembly instructions only after I've build the prototype). The next part was the most difficult, mostly because it's hard to see what's going on in both pictures and diagrams. The propulsion module is a mass of struts (just what what you want when modelling in card ...)   To be continued ... ? |

|

#5

|

||||

|

||||

|

Will be eagerly awaiting.

|

| Google Adsense |

|

#6

|

||||

|

||||

|

Good ideas here, and lots of good tips. I myself have tried (and mostly failed) to design in the past. Hopefully I can get something half as well made as your designs with some pointers.

My biggest problem so far is figuring out how to use the tools in PowerPoint (or Word, for that matter). |

|

#7

|

||||

|

||||

|

How to succeed without ...

Actually, I understand your point J - the key is to select designs without the kind of complex surfaces that require something like Pepakura or AutoCad. The drawing tools in PowerPoint (same ones are accessible in Word - harder to use due to display issues however) do the basic things that are hard (or tedious) to do by hand - precise measurements (use the snap to grid function), lines and shapes, perpendiculars, repeated operations (copy & paste), and coloring (you can manipulate the fill colors, add stock patterns, use photo textures, or even layer different effects using the transparency settings). Grouping lines and shapes into larger objects is also critical to create stable parts that can be moved around. Key is to just get started and try every button (we don't need no stinkin' documentation!) - saving frequently if it's an actual project.

So, the propulsion module. After looking at a lot of pictures it seemed to be four thruster sets connected by a maze of struts to a top frame and a bottom ring.  After a lot more staring, thinking, sketching and drinking it came to me ... each thruster set is attached by six struts. Four from the lower deck ring - two to the bottom of each thruster and two to the top corners. Two more from the top frame connect to the top of each thruster. The lower sets connect to the lower deck in four places, the top in four places rotated 45 degrees from the lower connection points. Being able to describe it leads to drawing in what the upper frame should look like - it's a square, which is not obvious from the drawings and pictures. This is why even a simple model is far superior to the best photo. For structural reasons I made it a circle and used graphics to outline the square frame. The bottom is a ring, which mounts to the Star 48 Venus orbital insertion motor. Basic dimensions were then taken from the side view of the stack - from that angle the thrusters are at the corners of a square so I drew in the square then drew the struts along the diagonals. Working on the bottom deck, I joined the two lowest struts to make them a little stronger, then added in slightly longer mid-struts since they attach at an angle (length was checked by making a side view, drawing in the struts, then taking those lines and moving/rotating them to the final part). Copy/paste ensured even and symmetric parts. The pieces were designed with a lot of overlap on the mounting to allow for trimming if needed. You can also adjust the angle of the struts and keep the thrusters vertical by bending or otherwise adjusting the lowest attachment point. The top deck was done similarly.   Then the hard part - how do you connect the upper and lower deck? Drawings show four sets of triangulated struts that connect to nodes with the thruster mounting struts. The key here is that we have the distance between decks from the photos/drawings and the positions of the top and bottom connections from the previous work on the thruster struts. Think of the triangulated struts as triangles (isosceles) - the base is the distance between strut connections to the bottom deck, the height is the slant height to the top deck. Don't forget, we have another set of triangles connected to the top deck. Their base is the distance between strut connections on the top deck and the height is the same as for the first set of triangles. Now we just have to butt the triangles' edges together and we we have our shape.  If you look at the plans (jleslie48.com under realspace downloads) you'll see I kept this part as an optional "strong" truss for often handled models (read little hands). To make a stick truss I simply drew the lines along the triangles' edges, grouped the lines into a part, and attached it to the top deck (more room there, bottom deck already had lots of crap hanging off of it). As always, this makes a very light and delicate part so I printed it on 110# card while the rest of the model is 60# (I tried to avoid gluing on little pieces of heavy card for reinforcement - too many little pieces in awkward places). The actual thrusters were modeled as simple boxes with one extended side to make attaching the struts easier and to model (approximately) what appeared to be a plume shield. I fiddled a bit with the nozzles because of their small size (should have used Jon's cone-o-matic). Eventually settled on something that's almost a cylinder but it seems to work.  A word on design work - open season here for the pros. I have to work out a rough sketch of major subassemblies to start with. Then, I figure out all the dimensions I'll need (if I can - some are, as noted, pulled from the process of drawing the actual model parts). Once I start on a subassembly I stick with it until that portion is done - if not I invariably forget some key detail or have to reproduce an entire chain of thought like figuring out those damn struts. Even if I complete the subassembly, I try to make a few notes to get the next one started. Regardless, I review everything I've already done before starting again on a new section - otherwise something is guaranteed not to fit or there will be a missing part. Finally, when it's all done I look at the parts arrangement. I try to keep subassemblies together and to line up duplicate parts (or any parts in general) so cut and score lines are lined up - you don't have to move the sheet around so much (repositioning straightedges, etc.) during the build (as I said - lazy, me). Are we there yet ... ? |

|

#8

|

||||

|

||||

|

Some thoughts on design ... and arrival

Unlike the pros (well, maybe not), I design my models for me to build - a bit compulsive and easily bored combined with a short attention span. This turns out to be a good match for school students (second childhood?) and I got started modeling again to make displays to promote science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education. So I figure I'm making a prototype for the students (or teachers, or other modelling enthusiasts) to make. That's my story and I'm stickin' to it!

All of this combined means I pay a lot of attention to keeping the parts count down, using graphics for low relief detail, and agonizing over the fit. The pros and experienced modellers can, no doubt, build-tweak-and-rebuild to make the perfect model, but a small person would likely give up and walk away forever. This also requires clear directions - Ton's sequential build photos are the gold standard here but I don't have the foresight or patience to do that. So, you get text - sorry. I also tend to use attached tabs (one less part) and make as many parts as possible fold-up pieces, without getting into serious origami. The Magellan bus is a good example of this. And, anytime the edges are attached as part of the overall model part you are guaranteed it will fit. Just finished a build with an octagonal box in it made up of separate top, bottom, and side band - 3 pieces. A tiny mismatch (still investigating whether it was me, the printer, or the model at fault) in the sizing resulted in two hours of agonizing, test fitting, and trimming (repeat many times) to finally get a good part. If the designer had done something like the Magellan's bus the fit would be guaranteed regardless of problems (shape may have ended up wonky, but it would fold up and fit). Fit is also where (just about any) drawing software shines. Once you make a 1/2" by 1" part of any shape you can duplicate it, drag it around, or rotate it and it will not distort. So, all this went into the final part of the Magellan - the launch stack. Magellan went up on the Shuttle (AXM has the mission) with an Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) and a Star 48 solid motor for Venus orbit insertion. They are well depicted on the dimensioned drawing and 'yer basic rocket is about as easy as it gets.   The diagrams show the solid as a cylinder capped with hemispheres and a nozzle, as well as the ring mount to mate with the Magellan. My first effort was a cylinder, two flat circular ends, and a cone for the nozzle. That level of (non)detail did not fit well with the look of the model, so I changed the ends to smaller circles joined to the central cylinder with frustums. Add a ring to mount and it's done. You could keep dividing up the ends into more frustums (those conic bands) and an ever smaller top circle - but more detail raises the parts count (for a auxiliary piece of the model) and results in ever smaller parts that would be difficult to handle. Above all, I want my models to be buildable by novices - with enough accuracy and detail to satisify (if not stimulate) more experienced builders. So the final result was a small circular top, one upper frustum, attachment ring (slips over the top), main body cylinder, one lower frustum, a small circular bottom, and a nozzle cone. This is also a good example of the initial design stage of breaking the model up into actual "parts." The IUS was a similar design, except for the shape of the top and (another!) set of struts. After studing all the diagrams (some artistic license evident) and photos there seemed to be six attachment points on the IUS and corresponding Magellan load ring. I pulled the dimensions, added the struts to the top of the IUS (plus enough length to fold over and attach), and there you go. Top circle with struts, upper (reversed) frustum (sets inside the main body), main body cylinder, lower frustum, circular bottom, and nozzle cone.   The hardest part (for me) in all of this is the 3-D visualization of connecting parts. My approach is to draw it from as many angles as possible - somewhere in there I get a flat on view (of at least a portion) that I can pull a shape or measurements from. And so, there we are. Comments and corrections from the pros are welcome - but more importantly, if I can do this so can you. If you can't find it - make it! Yogi |

|

#9

|

||||

|

||||

|

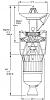

Ugly Picture #7

This is the alternate propulsion module with a solid core rather than struts (didn't use it but had the parts, so ...). I also trimmed away the upper circle - back to the mounting outline. If you just look at the edges of the central core, that's the final strut part. You can also see how the thruster support struts twist into place on the right side - also what a visual spider web it is in a picture. Solid part is actually almost obvious in how it works.

Yogi |

|

#10

|

||||

|

||||

|

Baiting the hook ... displaying the model

As I've said (tired of it yet?), my models are intended to stimulate interest in science, technology, engineering, and math - and, of course, have nothing to do with my personal enjoyment of the hobby. The sight of a display of aviation or space models tends to bring them in - but you need something more for context. You can set your models on a shelf at home, but for a display you need to present the model at a good viewing angle (able to see interesting details given the model's location/height and the viewer's sight line) and provide enough information to identify the model's original subject and significance.

So I make display bases. They're nothing fancy, just a dowel (or other model support), chunk of wood and a graphic. I try to select a graphic that provides both context (picture of destination planet) and information (what it is, where it is, scale, what's it done, why should you care, etc.). For Magellan, I pulled a graphic of the radar map of Venus made by the probe then positioned the probe with its radar altimeter feed horn pointing at the surface.  For a Mars Rover or Phoenix lander I printed an "overhead" mosaic made by the probes then folded the edges down to make a simple raised platform - this showed the model in the "same" place as the real probe. Nothing as fancy as Ton's Surveyor moon surface diorama or an Apollo landing complete with foot prints - but enough to engage the viewer.  For Voyager I used a graphic showing their mission trajectories and included current location info (billions and billions of miles); for Hubble a couple of "greatest hits" with the pillars of creation picture and the ultra deep field.   To actually attach the models to the base I usually use a dowel. Rockets just slip over a vertical dowel using holes (best pre-cut during the build) though the engine and lower formers. Spacecraft usually have a flat surface (solar panels) that can be slipped into the end of a split dowel. Sometimes (telescopes) you need to make a cradle - easily done by cutting 8 or so 1/4" wide strips of card and laminating them into a semi-circle using the model (protected by waxed paper) as a form. Glue on a little sleeve to fit over a dowel and you have a cradle.  So, any questions, comments, or suggestions ...? |

| Google Adsense |

|

|

|